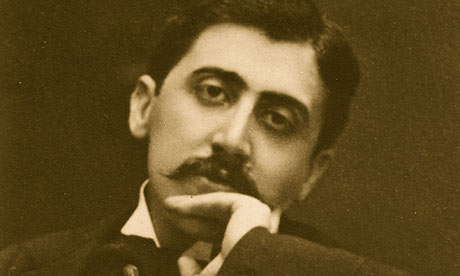

In the post before last, I told you how I met Proust when I was ten and a half while he was taking a walk near Combray, admiring hawthorn and Gilberte Swann. Anecdotally, he helped me look at hawthorn flowers: he mostly helped me look around me, look differently, read, and respect difference. As did Virginia Woolf.

I was no genius and did not understand “A la Recherche du Temps Perdu”. I did not even read the whole of it this spring and summer. I read “Du Côté de chez Swann” and was interested by Marcel because he was a child. I remember the stained glass of the church window with Geneviève de Brabant and la duchesse de Guermantes, a long passage where the Narrator was telling how Tante Léonie liked her potatoes – and that testifies both of my greed and of my fascination for the length of the passage (over two pages for one sentence!) -, the description of the sound of the bell over the rusty gate at Combray, Gilberte au jardin des Champs Elysées, these small things that were close to my life or that I could experience.

Later, I came back to “La Recherche”, book after book, with stumbles, hesitations, darts forward and re-reads, misunderstandings and non-understandings. One does not exhaust the reading of “La Recherche”, as of other great fiction. But I read the last volume, “Le Temps Retrouvé” with awe. It applies to my life, to my attitude to life, and I find it relevant to our days.

The Narrator is an adult and rediscovers a number of people he has known since his childhood, from afar or closer. And le baron de Charlus makes a sort of roll call of the protagonists, from the past and present, as some are dead and others … decrepit. All previous books have tended towards this moment. Time is “found back” (retrouvé) in the present. All that was before is the past. Only the last pages capture the essence of THE moment. But is Time found back or is it now lost? With a supreme irony, when Time is found, it is definitely lost. The quest to recover it (“A la Recherche du Temps Perdu”) is to find that it was lost while the Narrator was living it. And now that we are at the end of the quest, what we find is … nothing. Or, in any case, not Time as it was before. This is definitely lost.

I often turn back to my past. It was a time…

Yes, it was a time when I had a family, great-grand-parents, grand-parents, parents and other collateral members. Yes, I was a child, a young girl. There were summers that seem warmer than these summers. It was an easy and graceful life. It was a life of books and of music. A life of discussions. A life with friends and neighbours. A life where there were laughs, long shadows in the evenings, short shadows at noon, a cool house, a lovely garden, children shouting and running, flowers, pruned trees and fruits. What a life it was!

But was it?

What do I remember? Do I remember right? Was there truly such a time? There could not have been days like pearls on a perfect necklace of summery days. There could not have been only laughs. And if there was a cool house and a well-tended garden, there were people who did that. It could not have been plays, and music, and books only. The Little Family was already there: some people must have coped with their needs.

I remember Lost Time and would have it Present Time. But this is impossible. Like the Narrator, I listen to a roll-call of deaths: human beings, places, facts, they have all gone and perhaps never existed as I figured them out.

I remember them as I wish they would have been because I need them. I need to comfort myself with a dream that might have been true.

I turn to British (English?) novels that talk of this past time or a time that reminds me of “my” time: Mrs Thirkell’s “Chronicles of Barset”, Miss Read’s “Thrush Green” or “Fairacre”, novels of a time that was written in the first part of the twentieth century. Novels of past fights, of nostalgia, and I forget that, when they were written, they either already were fluffy eiderdowns or were talking of a reality which was not that cosy.

I forget that when these novels were “revived”, in the 1980s, the initiators of this revival wanted to root the present in the past. And, indeed, it is desirable to know the past in order to understand the present and to prepare the future. There is this maxim that one of my conservative great-aunts used to tell me: “the more you adapt yourself to things that change, the less these things change”. I discovered later that she was citing the Antonines and Lampedusa’s “The Leopard”.

Things must move on. We cannot hold time. It slips through our fingers like water or like sand. It does not repeat itself but in scrolls: never exactly different, never exactly the same.

This is a lesson for my personal life that I learn everyday with difficulty, in cahoots, with tears, with pain, with hurts.

This is also a lesson for countries and societies. We shall not come back to an idyllic time that was embellished by … time itself. The Antonines knew that they lived a moment of balance but that this balance was precarious. The Barbarians were to come and destroy the Roman world to build theirs. But were they Barbarians? And what did the Romans do to themselves? Were they not in part their own Barbarians? When Lampedusa makes his Prince Salina advise his nephew, Tancredi, about adopting changes to maintain the possibility of Salinas and Tancredis, what share of responsibility do the Sicilian aristocratic families carry in their own fall?

What is the West’s – and I mean all the First World nations – load of responsibility in its decline? What is Europe’s load of responsibility in its vagaries – and I mean the Continent Europe, not only the European Union -? Have we dreamt our pasts?

Better look at them squarely, learn from them, and go ahead. There is no point in dwelling fruitlessly upon the past. It never comes back.

I have never read Proust, but that is something I am always meaning to get around to. I love how you speak of summers being warmer in childhood – I feel the same thing too! I wonder if it is part of the human condition to imagine the past as being more beautiful than it was? A strange foible of the human psyche.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think it helps going through hard times. But it may become a severe delusion. First, we forget the present and think only of the past. Second, we beautify the past. Do not laugh if I say that Downton Abbey may have subconsciously help the Brexit. It was a pretty/prettified image of glories of Britain, which exalted all the unique virtues if the Briton. Was “being downstairs” so wonderful? Were the British the only ones to have qualities in their relatively little island? The French think of the glories of their revolutions and of their being the initiators of “liberty”. The British exalt the Empire. But we all have flaws in our pasts as we have flaws n our presents. I think it is the same for the individual and for the nations. We need the past to have roots and experience and understanding but we have to turn to the future.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very wise words. The ‘glory’ days are always remembered so fondly, without the realities of the every day problems. Having never seen Downton, I couldn’t comment on its influence over Brexit, but you could very well be right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I tell all my British friends that it might very well happen in France over a totally different past. There is a manipulation of people that is unhealthy in my country as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am sure it happens all over the world – and to think, we supposedly live in democratic societies! But even here, corruption and influence is rife and serves only the ruling classes. It is a scary time indeed, but I feel strangely elated to be living history right now.

LikeLiked by 1 person